QCEA - Quaker Council for European Affairs - the Quaker office based in Brussels, have just posted two blogs related to trends in Europe to do with the development of "defence" thinking in Europe.

While Brexit is not a focus of QCEA, our work on peace and human rights makes one thing abundantly clear to us: from foreign aid and migration policy to the global sanctions regime, the EU really is “the only game in town.” Funnily enough, the British government seems to agree.

The ‘Chequers Plan’ – the white paper which is still officially the UK’s negotiating position on Brexit – reads like a long list of reasons to remain. Indeed, as early as page three, the recently-appointed Brexit Secretary writes about building “unprecedented, unrivaled, unparalleled” partnerships in economics, security and data sharing. To achieve this, he says, “we will need a new model of working together that allows the relationship to function smoothly on a day-to-day basis.” Doesn’t that sound a lot like EU membership?

This is the contradiction which has caused so many problems for the white paper: it seems like a muddy, legally unworkable compromise which satisfies nobody. To Brexiteer Conservatives, the white paper’s contents represent a kind of “vassalage”, so intolerable that several have quit the government altogether in protest; for the EU, the document is just more of the same flagrant cherry-picking.

In a sense, both might be true. But amid the hubbub of discussion about customs agreements and the Irish border, important implications of the white paper are being overlooked.

*

The Brexit referendum was the conclusion to a decades-long campaign

of national hysteria about EU meddling, whipped up by a coalition of

journalists and politicians. Among their many breathless warnings was

the “secret German plot” to establish an EU army – a development which

was apparently just around the corner for twenty years yet never seemed

to transpire.

Although the concept of an “EU army” is something of a simplification, the Union has pursued rapid militarisation in the last 18 months. Wracked by internal disagreements about migraton, and faced with authoritarian nationalism at home and abroad, it’s perhaps little wonder that European governments are seeking to “go it alone” (with the global arms industry offering a nudge of encouragement, of course). The UK – faithful friend of NATO and allergic to any suggestion of European statehood – was the perennial thorn in the side of these ambitions.

Ironically, the British vote to leave the EU has been the impetus for militarisation to begin in earnest. Even more ironically, the British want in. As early as May 2018, HM Government was quietly publishing working documents which made clear just how enthusiastic the UK has suddenly become about EU military activity, even pledging to make “future contributions to EU Battlegroups”. (To be clear, “contributions” refers to human lives.) It seems the only thing less tolerable to the British than the existence of an EU army is being excluded from it.

The Chequers Plan, which was agreed by the Cabinet before being rubbished by many others, doubled down on the double standards. Among the British government’s shopping list for negotiations are:

- continued UK membership of the EU’s Political and Security Committee (PSC), which makes decisions on EU foreign policy, as well as the attendance of the British Prime Minister at some meetings of the EU27;

- continued involvement with the EU Military Staff (EUMS), as well “no drop-off” in existing cooperation on development funding and crisis management, and

- guarantees for arms trade supply chains to be uninhibited in the event of a “no deal” Brexit.

“The ability to protect citizens within Europe is increasingly intertwined with broader foreign policy, defence and development objectives outside Europe. It is necessary to have a single, coherent security partnership between the UK and the EU to address: the roots of terrorism and prevent attacks; identification of terrorists and efforts to bring them to justice; instability in the neighbourhood and work to prevent offering a haven for organised crime; migration challenges affecting Europe; the provision of development funding across the world; and the use of data in a range of contexts.” (Chapter 2.1.3)

Again, before becoming an advocate for “an unprecedented depth and breadth of cooperation to keep people safe”, the UK was vehemently opposed to any such collaboration at all, going so far as to negotiate opt-outs from justice and home affairs policies enshrined in the Amsterdam Treaty. In a Vote Leave pamphlet, pro-Brexit MP Michael Gove complained (wrongly) that these same EU policies mean Britain is unable to deport all of the people it may want to. So why did he vote to re-apply them in 2012, 2013 and 2014? And why did he back the Chequers white paper which endorses them so wholeheartedly?

*

The Chequers Plan is full of this hypocrisy. There can only be two

conclusions: either leading Brexiteers willingly played the public

consciousness or are now in damage-limitation mode, panicked by the

scale of Britain’s impending isolation.It’s undoubtedly true that Britain’s political class, like many of us, failed to understand the vastly significant role the EU plays in international security, humanitarian aid and foreign affairs more generally. Unless the UK’s vision of itself as a global player is to change drastically, it can ill afford to cut itself off from the European juggernaut. But for many of us – particularly Quakers – the Chequers Plan also raises difficult questions about what the European Union will look like in the years to come. It also reminds us of why Quaker voices in Brussels are important.

That Britain’s political hawks are suddenly so excited about European cooperation is a meagre endorsement of the EU in 2018. Whither peaceful cooperation?

The weight of expectation

*

Now is a good time to ask the question, as the EU and its member

states are currently finalising negotiations on the next Multi-Annual

Financial Framework (MFF), the Union’s budget for the next seven years.

What was already a complex diplomatic exercise has been rendered

trickier still by the impending withdrawal of the UK and its sizeable

budget contribution, as well as the spectre of populism and nationalism

which currently overshadows all European politics.We’ve already seen the British vision of the future at it prepares to leave: a Union of convenience, measured solely by its weight in gold (or gunpowder). And the UK isn’t alone. In this “time of unrest,” the idea of a securitised EU has friends among both federalists and sceptics. For the former, going it alone on military matters is the final frontier of “ever closer union” and a handy insurance policy against American unpredictability; for the latter, security cooperation at home and abroad is the deus ex machina for Europe’s permeable southern border.

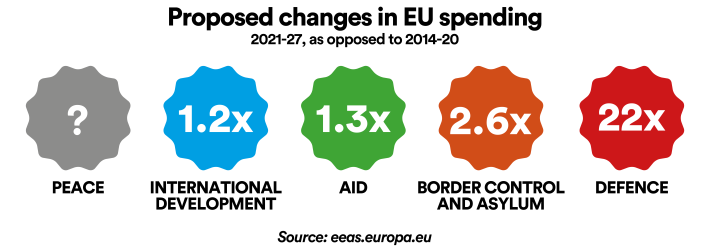

In the last few months, twenty-five EU member states agreed on Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), which devotes €13bn from the Union’s squeezed budget to military cooperation and defence research. More is set to come following the agreement of the MFF, which proposes to subsume vital funding for peacebuilding into a more general pot. In practice, this means that funding for true peace work may be sidelined, just when it’s needed most. And what’s more, these new arrangements would pour further billions into arming and training African armies without any oversight from the European Parliament.

Human rights and development funding fares better in the proposed new budget, rising by approximately 25% compared to the period 2014-2020. But when compared to the plans for a European Border and Coast Guard Agency, a European Union Agency for Asylum and their associated funds, the priority is clearly building walls rather than building bridges. The EU calls it “addressing the root causes of migration,” but among NGOs like QCEA it feels like the ghost of Fortress Europe is simply back to haunt us. Maybe he never went away?

*

It’s easy to read this and despair – wasn’t the EU meant to be about

making the world a better place; a spirit of brotherhood? Well, yes. But

it’s important to remember two things. Firstly, when the EU was

negotiating its last budget and accepting its Peace Prize in Oslo, the

world was a different place. Back then, its biggest concern was fiscal

stability in the wake of the Eurozone crisis. Brussels has now become

the forum for a totally different set of challenges. Which brings us to

the second point: we’re all guilty of ascribing too much agency to the

EU. We talk about its policies and decisions, its successes and

failures, but if anything it’s a mirror for the collective concerns and

interests of its members. And many of its members are currently in the

grip of xenophobia, populism and nationalism. If the EU is to right its

course and embody its founding values once again, national politics –

and voters across Europe – must wish it to be so.The EU is a major player in global affairs, shaping the world we live in by virtue of its size alone. But it is nonetheless a blank canvas, pulled taut in different political directions, on which a myriad of actors seek to chart Europe’s future course. It is up to us all to provide the compass; in Brussels, QCEA aims to show the way.

No comments:

Post a Comment